Refused a Second Date

Utopian Poetics # 7

I think the place I have to start when writing about Maya Williams’ second collection, Refused a Second Date, is to mention that it is genuinely one of the only full length books of poetry I’ve ever read front to back in a single sitting.

While writing about Frank: Sonnets, I brought up the question: “what kind of poetry do I actually want to be writing?” I felt a similar wondering with this book—and I regularly think the poetry collections I admire most are the ones that inspire me to write. Both Suess’ and Williams’ collections for me had a marked sense of energy that I felt really drawn to. I admired the poems in these collections for both their form and content, but there was something more than that. I really enjoyed the experience of reading them—I felt distinctly conscious of the pleasure I felt while reading these poems, even when the content of the work was at times really heavy. I don’t know that I’ve found (yet!) how to connect utopia with the way I find some poems are so pleasureful to read, but this is another book that had my utopian spider senses tingling.

In her blurb of Refused a Second Date, Diana Khoi Nguyen writes “This collection … reflects the truth of a present informed by history.” Gah! I know I keep referring back to Bloch via Muñoz and backwards glances, but this framing hits at something that feels so vital about this approach I’m reaching for. If the present in a poem can be seen as and informed by and full of history, I think it can also be seen as full of potential and futurity. The fullness of any present is what seems important. The point, I think, is that no moment is isolated. Every present moment is connected to both the future and the past. The multiplicity of every moment, every word—the way everything is loaded with connection and meaning. I’m reaching for a poetry that makes that sense of fullness visible.

I wrote about series of poems within a single book when looking at Diannely Antigua’s Good Monster, and here Williams has at least six distinct series of poems that make up the collection. Less than a handful of poems in this book can be taken as not directly connected to other poems via a series.

I also wrote in my last post about poetic obsession, the idea that a poet keeps writing the same poem over and over. As I read the series in this collection, I kept coming back to that question of obsession. If we are writing the same poem over and over again, what changes when we do so explicitly? What happens if I say “I’m going to write the same poem, but it’ll be different this time”? I think that’s part of the strength of this collection. One of the basic powers of poetry is holding space for a multiplicity of meaning in any piece of language. Every word could mean many things, and a poem makes space for all those meanings. Through their series of poems though, Williams takes this instinct a step further, holding multiplicities of meaning across time, context, and perspective.

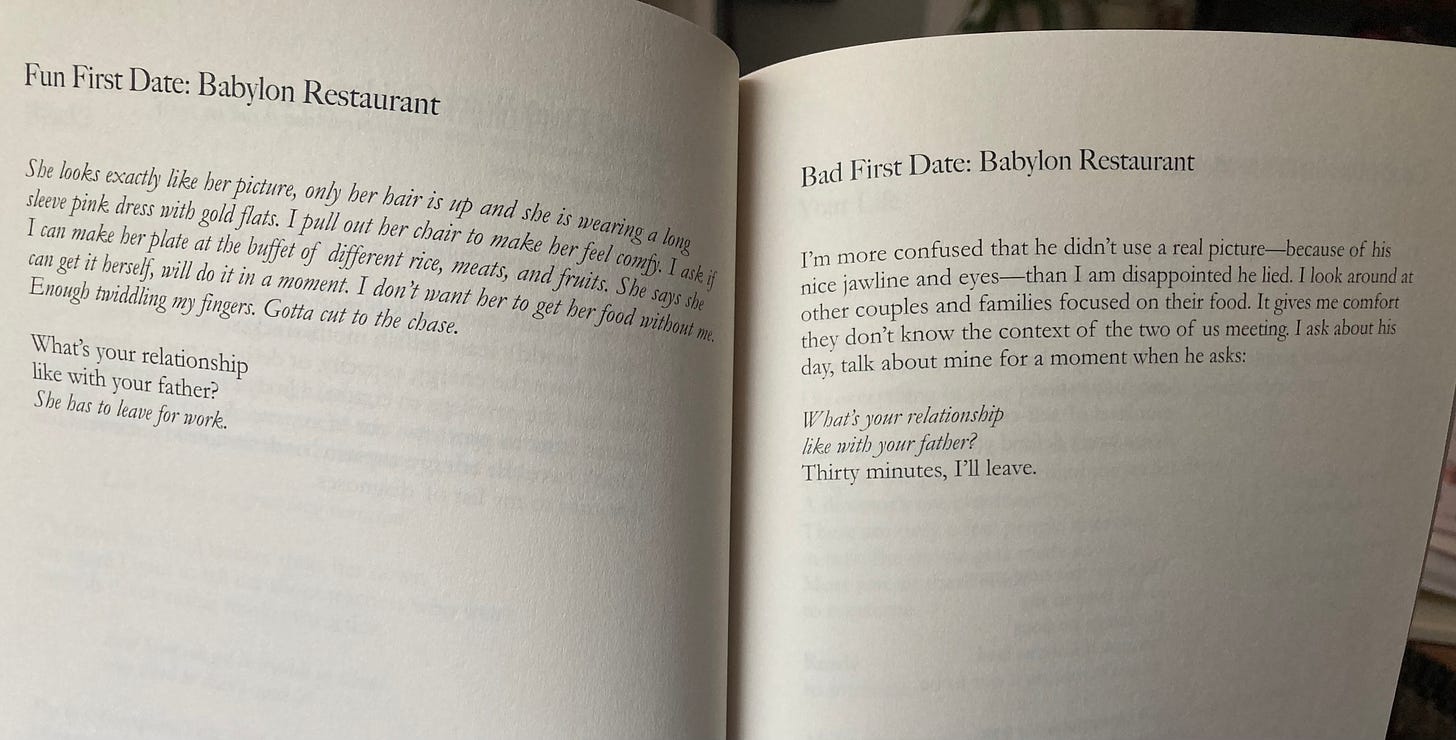

This multiplicity might be made most explicit through a series of poems about first dates. These poems are meant to be paired, with one perspective of the date facing an opposing perspective on the other page. Like this:

These poems run through a range of experiences, but they work to examine a single memory, a first date, from the perspective of the two people involved, each having a slightly different title to signal the difference in experience. In the act of writing two poems from distinct perspectives, these poems make visible the multiplicity of the moment—the way the various things that were said and done can be experienced so differently by each person, often the exact same language being taken in wildly different ways. And while these poems reflect such a basic human experience—the way a bad first date is so often rooted in severe misunderstandings and misreadings—I think these poems are making explicit the fullness of the moments they recall. And even more, the context of the surrounding poems in the collection is adding a fullness to each of these experiences. The way some of these first dates are racist or creepy is directly related to the content of the other poems. Returning to Diana Khoi Nguyen’s blurb—the present of the dates in these poems is informed by the history of the other poems in the collection.

And perhaps this is a reach, but these first date poems also capture the potential and futurity in first dates! By the final pair of poems, as a reader I’d been trained to expect something even worse to happen. Instead, we finally get “Best First Date,” the same title for each in the pair. Again, this poem is filled with the history of all the bad dates that preceded it. The history that a series of poems makes visible is so clear in this final poem of the series. That’s why we keep going on first dates after so many bad ones. And maybe that’s what a utopian poetics is reaching for—poems that make visible those moments of fullness where a futurity is clear, even after coming up short so many times.