When I first decided to write into the notion of a utopian poetics, I knew I specifically wanted to start with two collections: Diana Khoi Nguyen’s Ghost Of and Dianne Suess’ frank: sonnets. Both of these books have received plenty of praise in poetry world—I’m far from alone in loving them—but my personal experience reading these two books felt big. They’re both collections that I felt in awe of on a craft level, but also works I found a real sense of joy in reading. Suess’ book in particular set my mind wandering down a new line of thinking, particularly as someone who had been struggling to do much writing at all, a question that feels obvious, but I don’t think I’d stopped and asked myself in some time: what kind of poetry did I actually want to be writing?

Whereas in rereading Ghost Of I felt a quick clarity in what I wanted to write about, my recent reread of frank: sonnets has felt more evasive. I still love this book and these poems. No—I adore these poems. But putting my finger on the why I think these poems are so special has been more difficult. Perhaps there’s too much to say.

Suess’ poems throughout this collection seem to me to have some of the most refined attentiveness and energetic embodiment of what poets often refer to as “dream logic” that I’ve ever read. Poems often work through language via association, which feels similar to how our minds work, especially in our dreams. Words remind us of other words. Words remind us of memories. Memories remind us of memories. Memories and words remind us of ideas and words and memories. And so on. And while there is some logical connection driving these associations, it’s so often impossible to spell that out for someone else, especially as these connections feel fleeting with the speed and mystery of how our minds work.

I think this kind of attention to association most clearly manifests in metaphor—this one thing reminds me of another thing, and that connection helps me understand or reframe or challenge how I view both, whether the initial logic that drove the comparison is clear or not. But I think so often the sense of propulsion and movement in any poem is also associative. The beginning of a poem and its ending aren’t bound to being the linear beginning and ending that we associate with telling a story. It can be, but so often the ending of a poem is found via associative connections that can only be mapped back to the beginning via the associative dream logic working in the poem.

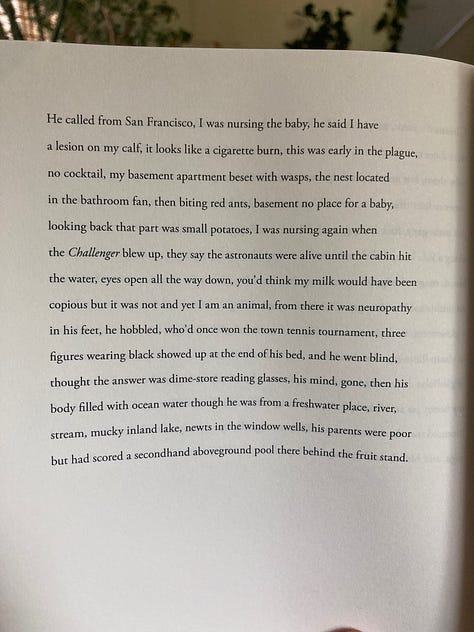

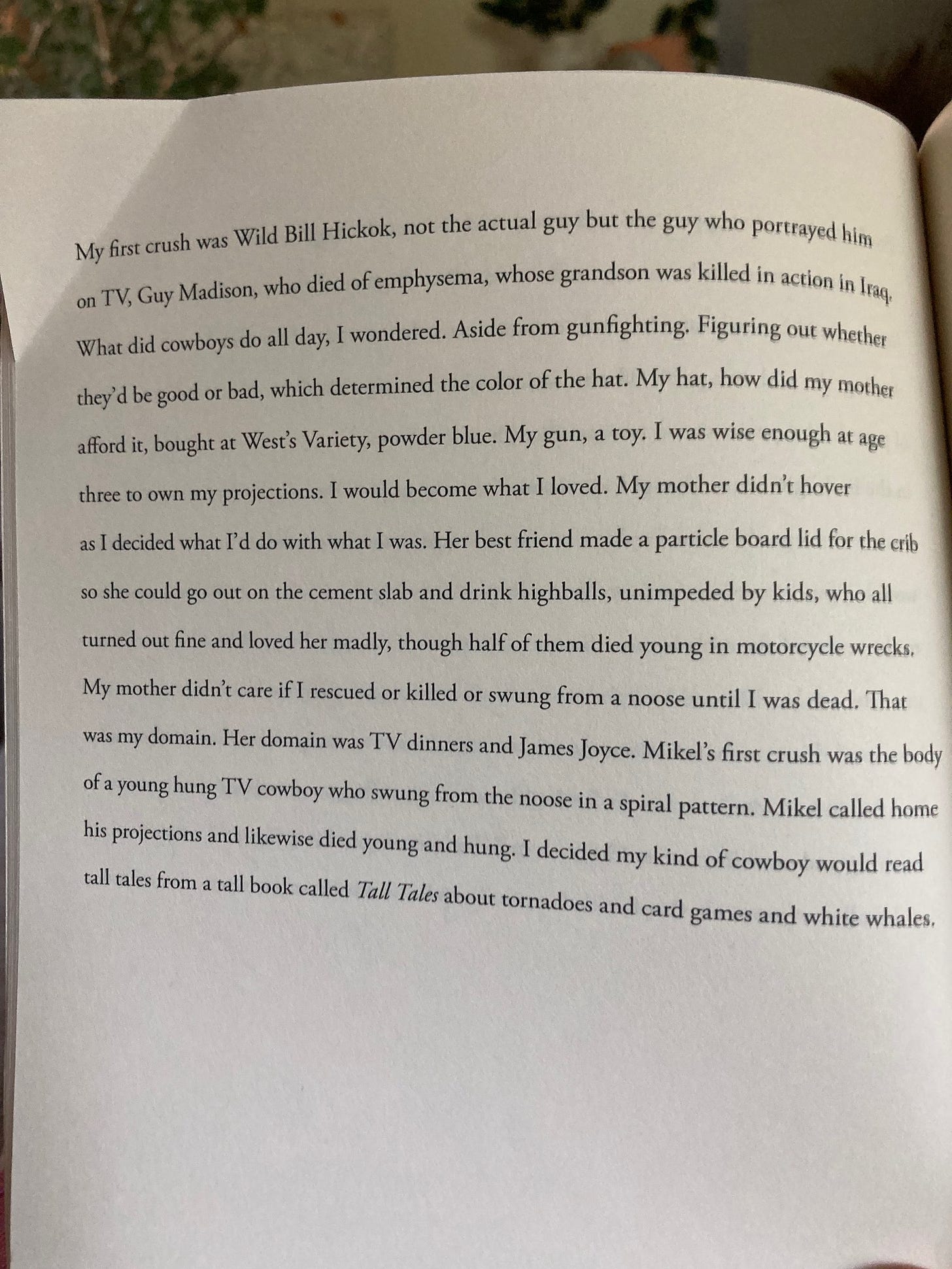

But what about the poems from this book, Bob? This is all so much easier to see in the action of the poems. Here’s one of many, many poems in the book I dog eared:

There is a circular logic to this poem (and plenty others in the book), moving from “My first crush” was a tv cowboy in the opening line to “I decided my kind of cowboy” in the final two lines, but there’s so much happening in-between those two thoughts. And like many of the poems in the collection, a lot of the in-between is spent thinking about death. But what I love so much about this poem and so many of Suess’ poems is the sense of momentum and energy as she jumps from thought to thought—as well as how clearly these associative jumps are spelled out for a reader. No movement in the poem feels random. Perhaps it’s sacrilegious to pull a poem apart this way, or too much like diagramming a sentence (woof), but here’s an attempt to quickly map this poem’s internal logic:

My first crush was Wild Bill Hickock (cowboy)

Not the real guy, the tv actor

Who died of emphysema (death, which we’ll return to)

Whose grandson was killed in action in Iraq (death, again)

What did cowboys do all day I wondered. Aside from gunfighting.

They’d (cowboys) figure out whether to be good or bad, determined by hat color.

My hat (the connection here), how did my mother afford it?

My gun, a toy (jumping from childhood hat to childhood toy).

I was wise enough at age three to own my projections. I would become what I loved.

My mother didn't hover.

Mother’s best friend made a particle-board lid for the crib so she could go out.

Her kids turned out fine, and loved her madly, though half of them died young in motorcycle wrecks (death returns)

My mother didn't care if I rescued or killed or swung from a noose until I was dead. That was my domain.

My mother’s domain was TV dinners and James Joyce.

Mikel's first crush (going back to the first line) was the body of a young hung TV cowboy (again back to the first line) who swung from the noose in a spiral pattern.

Mikel called home his projections (back to # 9 on my list) and likewise died young and hung (returning to death)

I decided my kind of cowboy would read tall tales from a tall book called Tall Tales

I think generally this kind of associative logic is fundamental to how a poem works, but there’s something really instructive in the way this poem wears its associations so clearly. Words and ideas are repeated in such a way that I feel a real grasp of how each thought jumps to the next, even though some of those leaps feel so far.

But I’m letting my awe for this poet and her craft get in the way of thinking about the utopian at work here. What am I trying to say? Suess’ work in this collection is autobiographical, explicitly looking to her past as the content of these poems. In these backwards glances, we see how memory is littered with associations that help recontextualize and understand the memory in new ways. I think this poem demonstrates how using an associative logic to consider memories gives us a model for how we might find what’s missing in the past (returning to José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia) and also how me might reach for what’s beyond the horizon of the future. The associative logic of a poem could give us a means for making connections beyond the logic of the present.

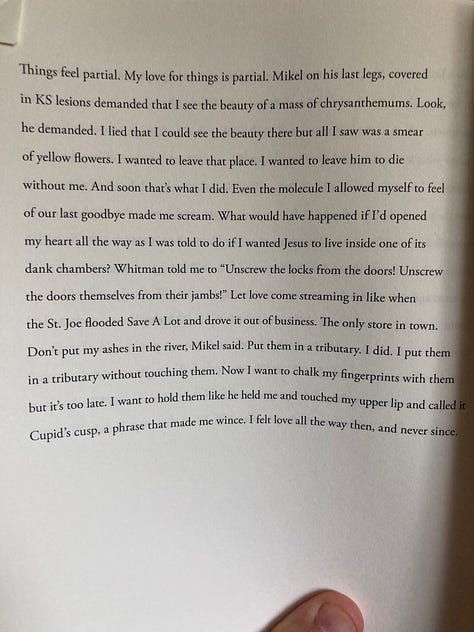

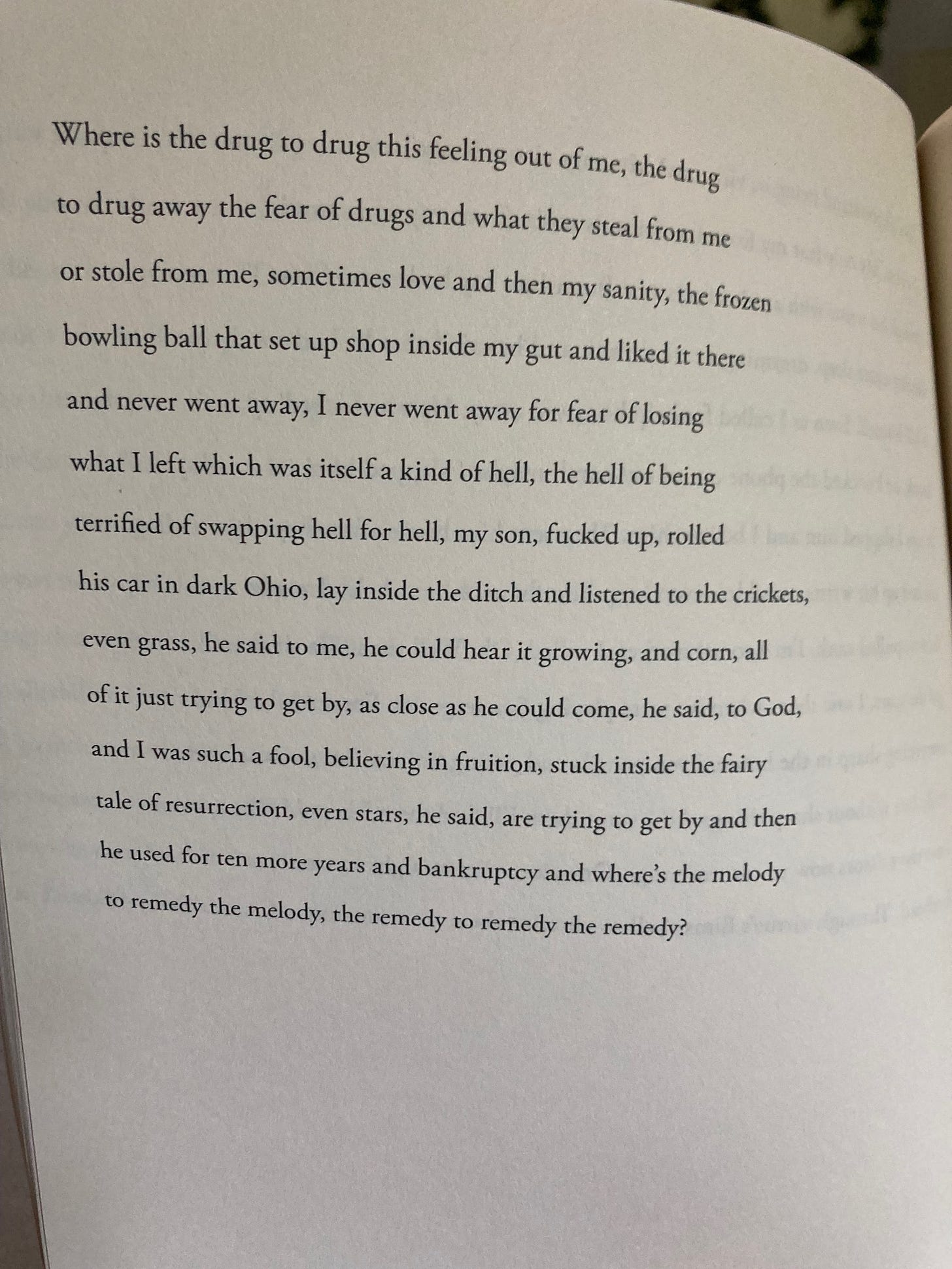

Here’s another one that I dog-eared that I think highlights some more of what I’m reaching for:

The repetition is so clearly leading the music of this poem, but it also highlights the way the poem moves associatively. I was going to try to do another sort of diagram with this poem’s repeated words, but there’s just so much music here. I felt like I was missing so many important connective moments if I didn’t focus on sound more broadly by looking at repeated sounds within words. And then as I retyped up each word that felt like it was musically stringing along the internal logic of the poem, I found myself rewriting the entire poem. Which is perhaps to say that this poem doesn’t waste a single word. The poems throughout the book have this sense of looseness that’s on display here, in part because of the run-on-ness of the sentences and the jumps in logic, but scanned closely every moment feels carefully tied together by repetition of words, ideas, or sounds.

Similar to the way Seuss is using association, the musical tools of a poem, like the repetition of words and sounds within words, allow for the memory to be considered in ways that it wouldn’t be in prose or a simple retelling—the connections that I’ve been so interested in are ones that perhaps can only be made through the act of writing the poem. Sound is leading the poet to make associations that might not be found otherwise. The poem doesn’t offer simple answers to explain or understand the memory, but uses sound to build new associations and ask new questions to see the memory through: Where is “the remedy to remedy the remedy?”

Thinking about sound in the poem brings me to form, which I’ve so far avoided. As the collection’s title announces, these poems are all sonnets. Earlier this year, there was a predictably silly and mostly unproductive argument about these poems as sonnets started by this tweet. And the poet who started the argument wasn’t alone in their reaction to these poems as sonnets. Some reviews from my library’s website:

1 Star: “14 lines of each enjambment doesn't sound or even look like a poem. sensible or not ramblings could be parsed in a verse less wordy to have stronger poetic effect.”

3 Stars: “Petrarch never wrote sonnets like this.”

I’m not particularly interested in the twitter discourse that followed (though it’s of note that Suess’ response was both insightful and gracious). My basic bias is anything written in 14 lines that even suggests a volta is at the very least engaging with the sonnet form. There’s a quick voice in these kinds of conversations that asks: why call it a sonnet if it’s not going to follow the rules of the sonnet form? But the sonnet has a long tradition of evolving and shifting. I’m generally disinterested in any sort of strict, dogmatic adherence to a set of formal rules because that feels so disingenuous to the actual act of writing a poem. I don’t think of inherited traditional form as a set of rules to perfect but as a set of guides that force me as a writer to make choices I wouldn’t normally make. To write in a formal tradition (and to write into the tradition of breaking a form’s rules) is to engage in the tradition of trying to bring things out in your writing that you might not have come across otherwise. For example—if I have to fit an end rhyme to fit the form, I’m going to reach for not just the exact right word, but for the exact right word that fits the rhyme scheme, a choice I might not have thought to make otherwise.

Of course, that directly brings me back to these sonnets, which of course don’t follow the rhyme scheme of traditional sonnets (or any rhyme scheme for that matter). Yes, there can be joy in the challenge of successfully meeting all the requirements of an inherited traditional form. But this is also art we’re talking about. The moment the form starts to constrain the poem too much, it’s time to forget the rules and let the poem find its own shape. I tell my students to give up on the form they’re trying or any assignment’s guidelines the moment they find themselves excited to take a poem in a different direction. I fear I’m still talking about this in such an amateur way. And maybe some of that same instinct is at stake here, but Seuss’ poems seem far, far too well constructed to be written from a place of running away from form.

Returning to the second poem above (“Where is the drug to drug”), I couldn’t look at the poem closely for very long without its meter making itself clear. I’ll spare you from trying to break it down in detail here, but most of the poem is written in iambic (like a traditional English sonnet) with plenty of substitutions. The first few lines are around seven feet (two beats per foot—you remember, right?) and the latter part of the poem has slightly longer lines of up to ten feet. So the lines are longer than the traditional English sonnet (and vary throughout the book, culminating in two poems with lines so long the pages need to fold out), but Seuss is clearly mindful of the poem’s meter and it’s relationship to the content of the poem. The rhythm of each line stretching longer as the poem goes is part of how it builds such momentum. Every time I read this one, I feel in awe of how much control she has over the speed I’m reading at. The poem starts with this sort of broader reflective question (“Where is the drug to drug this feeling out of me”), but then moves to this very specific memory of her son in a car accident in the context of his struggle with addiction. When the poem transitions to the specific memory (perhaps its volta!), it picks up speed and a sense of momentum in the way those lines grow longer with more pauses and short phrases broken up by commas. Rather than engaging with the form as a set of strict constraints, Suess feels tuned into the expectations of the form and seeking for ways to build from those expectations, both writing into and beyond the tradition.

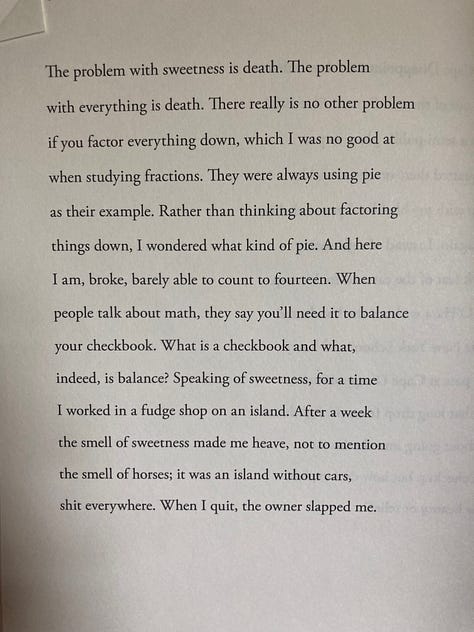

Here are three more poems that I hope help illustrate what I’ve been writing about:

I’m going to refrain from any more close reading, but looking at these poems helped me sum up what I think I’ve been reaching for. I think the poems in this collection are utopian in the way they reflect and model a range of possibility we can find in language that might only be accessible through the mechanics of poetry. These poems examine memory from a place of association, where connections are made both through dream logic and the musicality of language. They engage with traditional form not as a place of pure constraint, but a practice of using inherited form to build new possibilities. (Quick note: I like everything I just said, but I still think I’m missing something really important about the sense of energy in these poems). In the way Seuss’ sonnets examine memory, I find an approach for reaching into the past to look for possibilities beyond the horizon of the future—an approach built on associative logic, connections made through the music of language, and inherited form as a place of possibility rather than rigidity. In other words, these poems rip.

loved the deep dive, Bob <3